There's a new ankylosaur in town - meet Ziapelta sanjuanensis from the Cretaceous of New Mexico!

Hello, Ziapelta! Many thanks to new Currie Lab MSc student

Sydney Mohr for this wonderful life restoration of Ziapelta.

Ziapelta is represented by the holotype skull, first

cervical half ring, and assorted other osteoderms, AND a referred first

cervical half ring! (What are the odds of finding two really nice cervical half

rings in the same field season? Bonkers!) It's a wonderful find from an area that seems to keep producing interesting dinosaur fossils.

Surprisingly, Ziapelta doesn't seem to be particularly closely related to the other ankylosaurid from the Kirtland Formation, Nodocephalosaurus. Instead, it's a close relative of Euoplocephalus and friends from Alberta – it shares the same general shape and pattern of cranial ornamentation, with flat, hexagonal caputegulae rather than the round, conical caputegulae of Nodocephalosaurus. Ziapelta is distinct from all of the Albertan ankylosaurids though: it's squamosal horns are thick and curve slightly downwards laterally, and its median nasal caputegulum is huge and triangular, rather than hexagonal. Somewhat bizarrely, Ziapelta has slightly bulbous or 'inflated' looking cranial caputegulae, not to the same extent as some of the Mongolian ankylosaurids like Saichania, but definitely moreso than Euoplocephalus or Anodontosaurus.

Cervical half rings once again prove to be taxonomically

useful. Ziapelta has taller, more rectangular keeled osteoderms compared to

Euoplocephalus, Anodontosaurus, and Scolosaurus, but does share the interstitial

osteoderms present in Anodontosaurus.

Although we don't have the rest of the postcrania, we can assume that Ziapelta would have had a tail club since it is deeply nested within the clade of clubbed ankylosaurids. Did it have huge, triangular osteoderms like Anodontosaurus, a round tail club like Euoplocephalus, or a narrow tail club like Dyoplosaurus?

Ziapelta isn't the first ankylosaur described from New Mexico - in fact, it's just the latest in a string of interesting armoured dinosaur discoveries from there. At present, Glyptodontopelta is the only nodosaurid from the state, from the Maastrichtian Ojo Alamo Formation. It's known only from osteoderms, and mostly those from the pelvic region, but they're pretty distinctive and have a unique dendritic surface texture.

Nodocephalosaurus is known from a partial skull from the De-na-zin Member of the Kirtland Formation. Its nodular cranial ornamentation is totally unique among North American ankylosaurids and more closely resembles the Late Cretaceous Mongolian ankylosaurids - an intriguing biogeographical conundrum that remains unresolved.

Lesser known but deserving of more attention, my fellow labmate Mike Burns and colleague Bob Sullivan recently named another ankylosaurid from the stratigraphically lower Hunter Wash member of the Kirtland Formation. Ahshislepelta has a weird scapula with a strongly folded-over acromion process, as well as various other bits and bobs of the postcrania. Although there is little overlapping material between Ahshislepelta and Ziapelta, Ahshislepelta's osteoderms have a smoother surface texture, and the stratigraphic separate suggests we're probably looking at two different species.

Ziapelta is also neat because it (and Nodocephalosaurus) occur in a slice of time where we don't have very good ankylosaurid material in Alberta. In Alberta, we're in the lower part of the Horseshoe Canyon Formation – probably Anodontosaurus was found here around that time, but we don't have too many good specimens. Was it possible that Ziapelta roamed through the lower HCF? Or, are Ziapelta and Nodocephalosaurus characteristic of a southern Laramidian dinosaur fauna, like we seem to be seeing with some of the slightly older formations in Alberta (Dinosaur Park Formation) and Utah (Kaiparowits Formation)? Only more specimens will help us answer those questions.

Although we don't have the rest of the postcrania, we can assume that Ziapelta would have had a tail club since it is deeply nested within the clade of clubbed ankylosaurids. Did it have huge, triangular osteoderms like Anodontosaurus, a round tail club like Euoplocephalus, or a narrow tail club like Dyoplosaurus?

Ziapelta isn't the first ankylosaur described from New Mexico - in fact, it's just the latest in a string of interesting armoured dinosaur discoveries from there. At present, Glyptodontopelta is the only nodosaurid from the state, from the Maastrichtian Ojo Alamo Formation. It's known only from osteoderms, and mostly those from the pelvic region, but they're pretty distinctive and have a unique dendritic surface texture.

Glyptodontopelta bits at the Smithsonian.

Nodocephalosaurus is known from a partial skull from the De-na-zin Member of the Kirtland Formation. Its nodular cranial ornamentation is totally unique among North American ankylosaurids and more closely resembles the Late Cretaceous Mongolian ankylosaurids - an intriguing biogeographical conundrum that remains unresolved.

Nodocephalosaurus holotype skull at the State Museum of Pennsylvania. Check out those conical caputegulae!

Lesser known but deserving of more attention, my fellow labmate Mike Burns and colleague Bob Sullivan recently named another ankylosaurid from the stratigraphically lower Hunter Wash member of the Kirtland Formation. Ahshislepelta has a weird scapula with a strongly folded-over acromion process, as well as various other bits and bobs of the postcrania. Although there is little overlapping material between Ahshislepelta and Ziapelta, Ahshislepelta's osteoderms have a smoother surface texture, and the stratigraphic separate suggests we're probably looking at two different species.

Ahshislepelta holotype scapula at the State Museum of Pennsylvania.

Ziapelta is also neat because it (and Nodocephalosaurus) occur in a slice of time where we don't have very good ankylosaurid material in Alberta. In Alberta, we're in the lower part of the Horseshoe Canyon Formation – probably Anodontosaurus was found here around that time, but we don't have too many good specimens. Was it possible that Ziapelta roamed through the lower HCF? Or, are Ziapelta and Nodocephalosaurus characteristic of a southern Laramidian dinosaur fauna, like we seem to be seeing with some of the slightly older formations in Alberta (Dinosaur Park Formation) and Utah (Kaiparowits Formation)? Only more specimens will help us answer those questions.

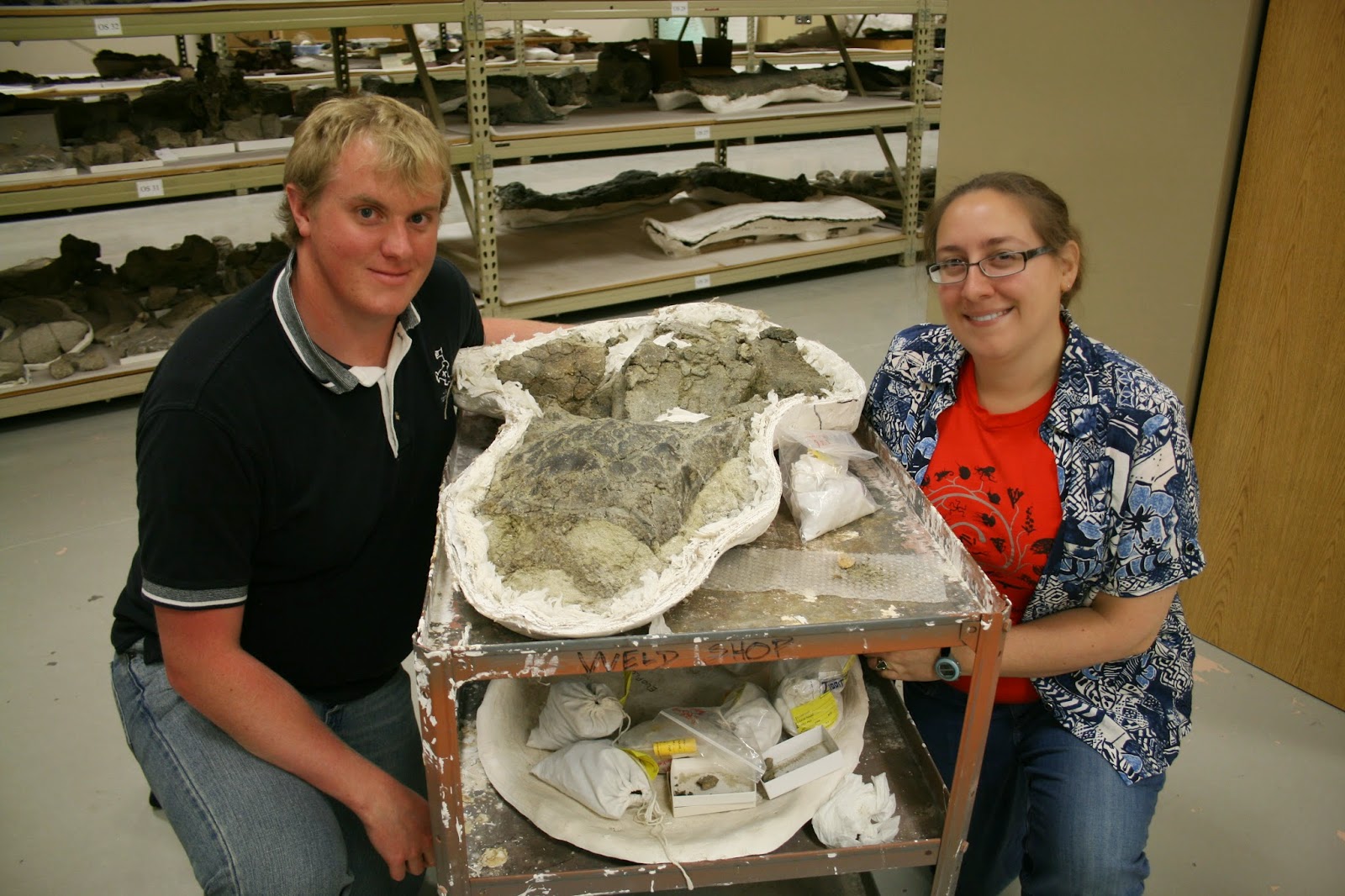

I'm very grateful to Bob Sullivan, who found these

specimens, for inviting me to help out with this paper, and to Spencer Lucas at

the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science for his hospitality during

my visit in 2012 to study the specimen. I hope one day I can have a chance to

do some fieldwork in New Mexico, although I fear my thick Canadian blood would

not serve me well and I would pretty much immediately die from the heat. Mike Burns and I

had a great visit to Albuquerque in June 2012 to study the specimen, but boy

howdy was it hot there. Ziapelta is housed at the New Mexico Museum and will be

on display there, so if you're in the neighbourhood go say hi for me!

You can read all about Ziapelta in our open access paper in PLOS ONE!

Arbour VM, Burns ME, Sullivan RM, Lucas SG, Cantrell AK, Fry J, Suazo TL. 2014. A new ankylosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Kirtlandian) of New Mexico with implications for ankylosaurid diversity in the Upper Cretaceous of western North America. PLOS ONE 9:e108804.

Ninja-edit! I would be severely remiss in not linking to some of the thoughtful news coverage we were very lucky to receive for this paper!

* Brian Switek covers our research at Laelaps: "Ziapelta - New Mexico's newest dinosaur."

* Hear my weirdo voice on the CBC's Edmonton AM!

* And via the University of Alberta, "New dinosaur from New Mexico has relatives in Alberta."

More papers!

Burns ME, Sullivan RM. 2011. A new ankylosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, with comments on the diversity of ankylosaurids in New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 53:169-178.

Ford TL. 2000. A review of ankylosaur osteoderms from New Mexico and a preliminary review of ankylosaur armor. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 17:157-176.

Sullivan RM. 1999. Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis, gen. et sp. nov., a new ankylosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation (Upper Campanian), San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19:126-139.