I've covered many of the North American ankylosaurs in my

previous papers and blog posts. In 2013, I argued that what we thought was

Euoplocephalus was more likely 4 taxa – Anodontosaurus, Dyoplosaurus,

Scolosaurus, and Euoplocephalus proper. Then in 2014 we described a newankylosaurid, Ziapelta, from New Mexico. There are a few other taxa that had

previously been proposed to be ankylosaurids, so let's take a look at them

here.

Aletopelta, Stegopelta and Glyptodontopelta

Aletopelta is one of the more tantalizingly enigmatic

ankylosaurs from North America. It's from a weird place – California – which may

have been much further south 75 million years ago compared to its current

position. It was also found in marine sediments, and the decaying carcass had

formed a little reef, with oysters encrusting the ribs. The only known specimen

of Aletopelta is relatively complete, all things considered, with the osteoderms

in situ over part of the pelvis, the legs partially articulated, and with

various odds and ends like osteoderms and vertebrae. Unfortunately, the ends of

the bones are often chewed apart, and some of the material is a bit hard to

interpret.

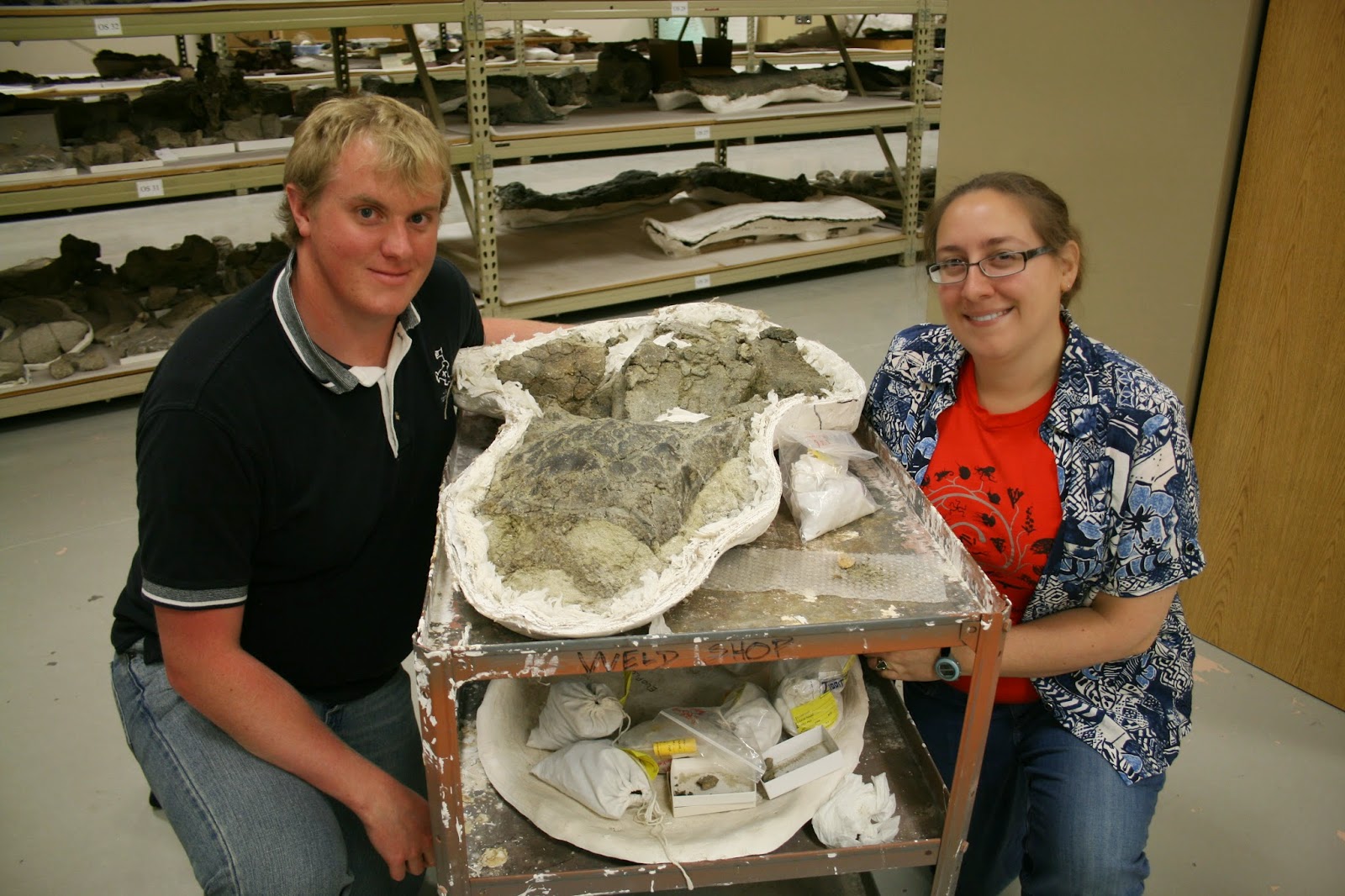

Here's the articulated pelvis and hindlimbs, and some other armour pieces, on display at the San Diego Museum of Natural History.

Regardless, Aletopelta is a very interesting ankylosaur. It

has an unusual osteoderm morphology over the pelvis, with small hexagonal

osteoderms closely appressed to each other. Ankylosaur pelvic armour seems to

come in two major flavours: fused rosettes, like we saw in Dongyangopelta and

Taohelong (and perhaps most famously in Polacanthus), and interlocking

hexagons, like in Stegopelta, Glyptodontopelta, and Aletopelta. Tracy Ford

suggested that ankylosaurs with these hexagonal pelvic shields might represent

a clade (dubbed Stegopeltinae) of ankylosaurids. Glyptodontopelta has since

typically been interpreted as a nodosaurid, as has Stegopelta, but the most

recent interpretation of Aletopelta was that it was an ankylosaurid. In the revised phylogeny in my new paper, we found

Stegopelta and Glyptodontopelta as nodosaurids, but Aletopelta as a very basal

ankylosaurid. However, although Ford and Kirkland reconstructed Aletopelta with

the typical ankylosaurid tail club, I don't think that it possessed one: the

preserved distal caudal vertebrae don't show any of the lengthening or other

modifications that are characteristic of ankylosaurid handle vertebrae.

An updated restoration of the known elements in Aletopelta - the main differences between this and Ford and Kirkland's reconstruction are the absence of a tail club, and uncertainty over what the head should look like.

Cedarpelta

Cedarpelta is an important taxon for understanding the

biogeography and evolution of ankylosaurids, and I wish we had more specimens!

I don't have many new comments to add about this taxon, since Ken Carpenter

published a great description of the disarticulated skull back in 2001. Cedarpelta

has been interpreted as a shamosaurine ankylosaur, as a relative of taxa like

Gobisaurus and Shamosaurus (which I'll talk about in the next post) from Asia,

and thus may point towards a mid Cretaceous faunal interchange between these

two continents. In our revised phylogenetic analysis, we didn't find Cedarpelta

as the sister taxon to either Gobisaurus or Shamosaurus, but it does come out

as a basal ankylosaurid in their general neighbourhood, and I honestly wouldn't

be surprised if future analyses or new taxa show support for it as a

shamosaurine ankylosaur after all.

Nodocephalosaurus

Nodocephalosaurus! What a fun ankylosaur. It's really quite

unlike the other ankylosaurids from North America, which typically have flat,

hexagonal cranial ornamentation. Instead, Nodocephalosaurus has bulbous,

conical cranial ornamentation. Bulbous cranial ornamentation is typical of

Campanian-Maastrichtian Mongolian ankylosaurs like Saichania and Tarchia, but

in those taxa the ornamentation is pyramidal rather than conical. The front end

of the snout in Nodocephalosaurus is also unusual, because there's no obvious

narial opening and instead the ornamentation has a stepped appearance.

Hopefully better specimens with more complete snouts will resolve this weird

morphology. I've also reinterpreted the position of the quadratojugal horn

compared to Sullivan's original figures – the horn should be rotated forward so

that the bottom margin of the orbit is complete.

Nodocephalosaurus holotype skull in dorsal and left lateral views.

Tatankacephalus

I don't have much to say about Tatankacephalus because I

didn't look at the original material myself, but the previous phylogenetic

analysis by Thompson et al. recovered it as a nodosaurid rather than an

ankylosaurid as originally suggested by Parsons and Parsons, and we found the same result. Overall, Tatankacephalus is VERY

similar to Sauropelta, so this is perhaps not surprising.

Up next: More odds and ends, but after I return from Utah!

Arbour VM, Currie PJ. In press. Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

Arbour VM, Currie PJ. In press. Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.